Proofreading Comics with Madeleine Vasaly

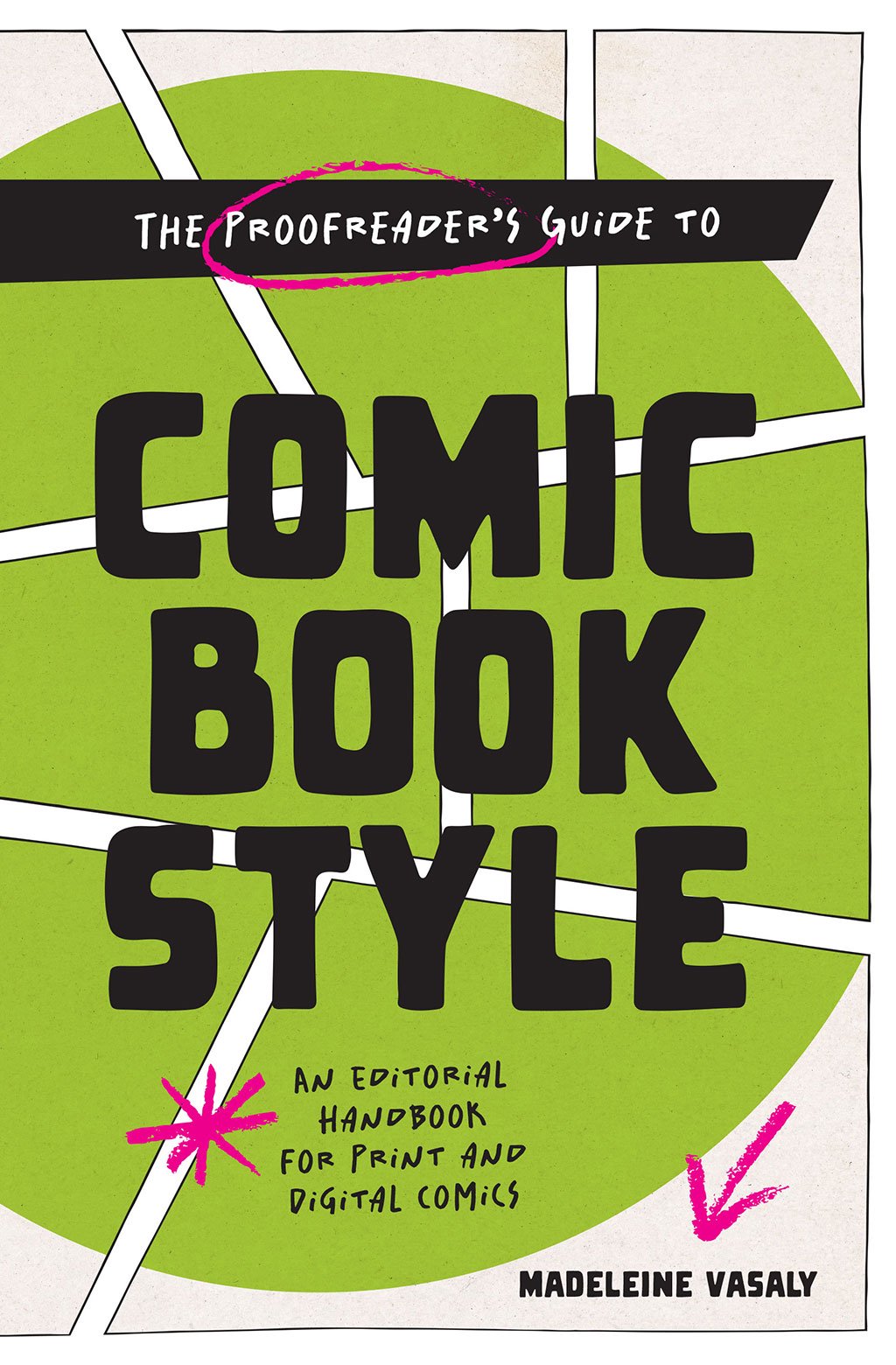

The Northwest Editors Guild blog team had the fabulous opportunity to chat recently with Madeleine Vasaly, editor, proofreader, and author of The Proofreader’s Guide to Comic Book Style. We’re excited to share with you everything we learned from that discussion.

Q: To start with, what got you interested in proofreading comics?

A: I started my career in trade nonfiction books, but I’ve always tried to take any opportunity to branch out into other categories, genres, and media types that interested me. Online news and prose fiction were first, but when the chance came to dip my toes into comics, I jumped at it. Besides the fact that I love learning new things, there’s a lot about comics that’s inherently fun—both the form and, a lot of times, the content.

Q: Have you always been a comics fan? Who are your favorite authors and artists?

A: I read the newspaper strips every morning as a kid, and some manga and webcomics as a teen, but I actually didn’t get into Western comic books and graphic novels until I was an adult.

I always have a hard time with “favorites” questions, so instead I’ll tell you the best thing I’ve read recently: Trung Le Nguyen’s graphic novel The Magic Fish, which had been on my to-read list for a while. The art is gorgeous, and I’m a sucker for stories that incorporate fairy tales in interesting ways.

Q: We understand that “editor” means something different in comic book publishing than it does in the more mainstream publishing world. Can you help us understand that difference?

A: In prose publishing, “editor” is often an umbrella term—people might use it to mean an in-house acquisitions editor at a book publisher, an assigning editor at a newspaper, a freelance copyeditor, or any number of other things. In comics, “editor” is a specific role whose closest prose equivalent is an acquiring or commissioning editor for books, but there are naturally some differences. Comics editing generally involves not only developmental work for the script but creative direction for artwork, among other things.

Q: Can you give us a quick sense of how the comic book publishing workflow differs from the workflow of, say, a prose fiction title?

A: Probably the biggest difference is that copyediting isn’t always a step in the comics publishing process. It’s typical for the work of copyediting to be effectively split between the main editor and the proofreader, which has a couple of implications for the proofreader. The first is that their scope is sometimes a little broader than in prose—for example, in some workflows it wouldn’t be out of line to suggest that a line of dialogue be rephrased for reasons other than an outright error, whereas in prose that would usually be overstepping at the proofreading stage. Another is that there might be more basic mechanical errors to clean up, like typos and punctuation errors, than there would be in a typical prose book.

The other important difference is, of course, the art and lettering. A comic might be written, drawn, colored, and lettered by the same person, or a different person might do each of those steps. Some steps happen in sequence, like pencilling coming before inking, but others can happen at the same time, like lettering and coloring.

Q: Do you typically proofread on screen, or with physical pages? What kind of program or format are you working in?

A: I’ve proofread prose on paper as recently as 2021, but that client is an outlier, and I’ve never worked on hard-copy proofs in comics.

I’m usually working on PDFs in Acrobat. Depending on the client, I might be doing my markup entirely with digital stamps and text boxes or with a combination of freehand markup (usually using my graphics tablet), highlighting with comments, “sticky notes,” and other tools.

For comics destined for digital publication, you might still be using PDFs, or you could be looking at image files or reviewing material on a dedicated online platform.

Q: What are a few of the most significant ways that proofreading comics differs from proofreading traditional manuscripts?

A: It differs in both style and scope. I’ve already mentioned that scope can be broader when there’s no dedicated copyeditor, but of course there are also things besides the text itself to worry about. For example, the proofreader needs to carefully review the speech balloons and caption boxes: Are the balloon tails pointing to the right speakers? Are the right balloon and caption styles being used? Are the margins between the text and the edge of the balloon consistent? Then there’s the artwork: Besides keeping an eye out for any words that are part of the art, you might also need to review continuity more or less carefully depending on the client.

On the style side, a number of conventions are widespread in comics but uncommon or nonexistent in prose. The capital letter “I” gets special treatment depending on how it’s being used. Two hyphens are completely acceptable in place of an em dash. And there are special symbols like breath marks, which can frame nonword sounds like sighs and grunts. Just to name a few.

An interior page of The Proofreader’s Guide to Comic Book Style shows examples of text balloons and how they can be used.

Q: What’s your favorite difference between comic style and prose style (either AP or CMOS)?

A: I love the way comics use things like capitalization, typeface, size, and balloon style to communicate tone. Because they don’t have dialogue tags or the other cues you’d see in something like a novel, the way the words themselves look does a lot of heavy lifting in conveying how a character is speaking. The right lettering can be really evocative, not to mention beautiful.

Q: Can you briefly explain why there are two different capital letter I’s used for different situations in comics?

A: The two types of capital I in comics are the slash I, which is just a plain vertical line, and the crossbar (or barred) I, which has the horizontal bars on the top and bottom.

It’s mainly tradition these days, but the story goes that back when comics were printed on newsprint and other low-quality paper stock, a slash I by itself could risk disappearing on the page if the ink didn’t take well or layers of ink weren’t properly aligned. Using the crossbar I for the personal pronoun would help make sure it was legible even in those circumstances.

Using the crossbar I within an all-caps word usually makes it harder to read rather than easier, and it isn’t considered good practice. But some publishers also use the crossbar I for things like Roman numerals, proper nouns, and the first word in a sentence. Everything else gets the slash I.

Print quality is much higher these days, and a lot of comics are published digitally, so losing an “I” isn’t as much of a worry anymore. But crossbars can still help with readability, and at this point it’s a well-established convention to use the crossbar I in the contexts mentioned above. Even though most mainstream comics publishers still maintain this distinction, you’ll sometimes see slash I’s for everything.

Q: Was there anything that was particularly hard for you to get used to when you transitioned from prose fiction to comics?

A: Probably the scope. On the one hand, as I’ve mentioned, as a proofreader you’re sometimes allowed and even requested to mark changes that in prose are usually the domain of the copyeditor. On the other hand, comics tend to be a casual and rule-breaking form, so publishers often allow wide latitude for things that don’t follow “standard” style as defined by a style manual or even a publisher style guide. And on top of everything, each client is obviously different.

Q: How would you advise editors who are interested in breaking into comic book proofreading?

A: It’s important to understand the editorial style conventions of comics and how they’re different from prose, as well as the differences among different forms of comics—comic book series, graphic novels, webcomics, zines. At the same time, as mentioned above, you need to develop a feel for when style (or grammar) should be enforced and when something should be left alone. It can be easy to slip into overediting.

Q: Do you have any recommendations for editors who would like to expand their comic or graphic novel reading, particularly if they’re maybe not well read in this field?

A: My philosophy is that it’s usually more important to read widely than to read specific works—there are a lot of different forms of comics, and a lot of genres and topics. I love superheroes as much as anyone, but you can explore drama, horror, romance, autobiography, history, or anything else you might think of in prose publishing, but explored in different ways. The writing, editing, artwork, and lettering can be radically different.

That said, there are plenty of titles that are important because of their cultural influence, artistic innovation, or historical significance. If you’re not sure where to start, you can find recommended reading lists that other people have created, or you can browse recent winners of the Eisner or Harvey Awards.

Madeleine Vasaly, the author of The Proofreader’s Guide to Comic Book Style, is a developmental editor, copyeditor, proofreader, and consultant with over a decade of experience in publishing. Her comics background includes a temporary stint at DC Comics as a full-time proofreader in addition to freelance work for DC, IDW/Top Shelf, Yen Press, Tapas, and other publishers. She has worked on series, one-shots, anthologies, graphic novels, and collected editions across all age ratings and created company-wide style guides for publishers. Outside her work in comics, Madeleine has edited and proofread hundreds of prose books and countless articles for online newsrooms. You can find her online at her website.